Density functional theory (DFT) is one of the most popular computational methods for predicting the properties of chemical systems, including atoms and molecules. The underlying premise behind DFT is that the energy of a molecule in its ground state, E0, can be determined from the electron density, ρ.(1) For that reason, DFT attempts to calculate the ground state energy and other ground state molecular properties from the ground state electron density,(2) without using the wave-function of the system. This can be mathematically expressed as:

E0 = E0[ρ0]

The demonstration of this theorem was first proved in 1964 by Pierre Hohenberg and Walter Kohn.(3) Its application is centered on the availability of exact solutions for idealized many electron problems, precisely an electron gas of uniform density.(4) Kohn and Sham(5) developed a practical application of this method, analogous in mathematical formalism to the Hartree–Fock (HF) method. These contributions by Hohenberg, Kohn, and Sham in the mid–1960’s laid the foundation for the present-day revolution in DFT. Over the past few decades, DFT has in fact conquered the rational minds of both computational and quantum chemists alike, consequently becoming a very popular method in the field. The method has made its way to the forefront of quantum chemistry and is a major computational workhouse that is commonly adopted in addressing some of the many exciting questions that arise in modern chemistry.(6) For his development of the density functional theory, Walter Kohn(7) was a co-recipient of the 1998 Nobel Prize in chemistry(8) with Sir John Pople,(9) who made the method accessible through popular computational packages like Gaussian.(10)

DFT calculations can be very accurate and offer significantly lower computational cost than other model chemistries such as the Møller–Plesset and configuration interaction models. Despite taking electron correlation into account, DFT calculations employ computing power similar to that of the HF method in executing more complex and larger molecular systems — a unique advantage the method offers when compared with other post-HF methods. This is regarded as a sensational feature of the method since results for a wide spectrum of physical quantities are obtained at a correlated level with excellent accuracy at a relatively low computational cost.

The formulations of the terms that make up the energy of density functional models are very similar to the Hartree–Fock energy terms. The only difference being that in the DFT energy term, the so-called exchange/correlation energy, EXC, replaces the exchange energy, EK, in the HF energy term. The DFT energy can thus be simply expressed as:

EDFT= ET + EV + EJ + EXC

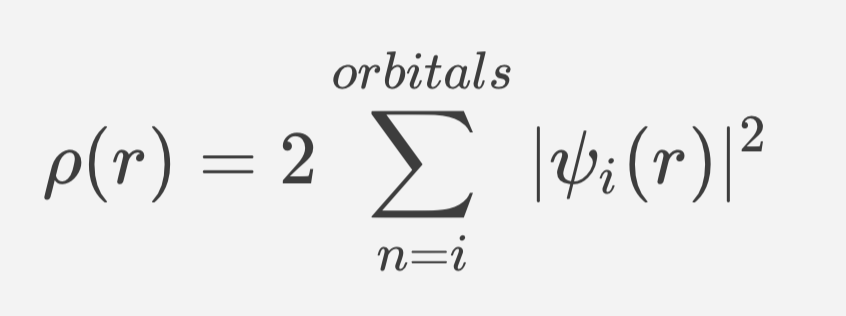

where ET, EV, EJ and EXC represent the kinetic energy, electron-nuclear potential energy, Coulomb energy, and the exchange/correlation energy respectively. With the exclusion of the kinetic energy term, ET, all components of the EDFT depend on the total electron density, ρ( r ):

where 𝜓i are orbitals strictly analogous to the molecular orbitals in the HF model theory. Minimization of the EDFT term with respect to the unknown orbital coefficients yields a set of matrix equations analogous in form to the Roothaan-Hall equations, that is referred to as the Kohn–Sham equations:

Fc=ε𝑆c

where F is the Fock matrix similar to the Hamiltonian in the Schrodinger equation, c is the unknown orbital coefficient, ε is the orbital energy and 𝑆 is the overlap matrix.

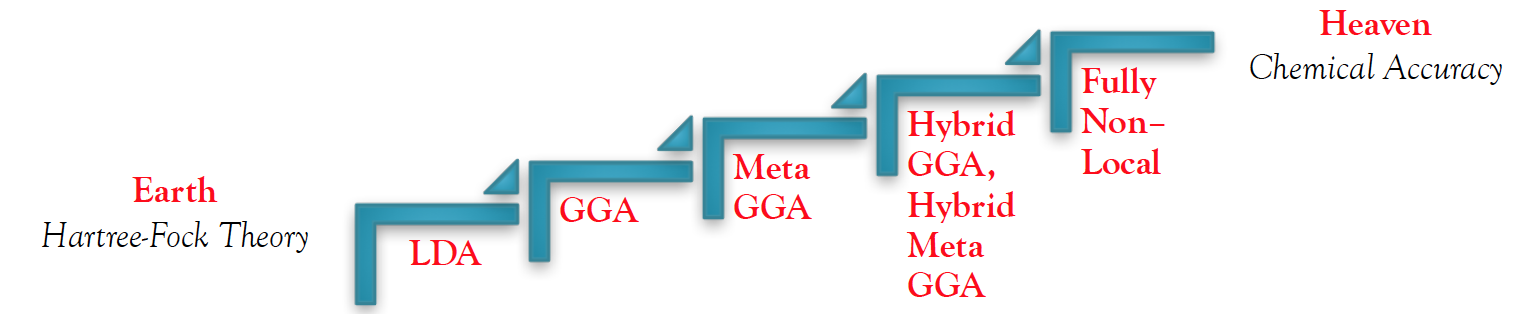

The DFT method is dedicated towards designing functionals which relate the electron density of a system with its energy. These functionals can be broken up into several classes according to their intrinsic functional dependencies and level of sophistication. The simplest density functional is the local density approximation (LDA),(5) which is based on the implicit assumption that the exchange-correlation energy at any point in space is a function of only the electron density at that point in space. As a result, a homogeneous electron gas of the same density can be used to represent LDA functional methods. The second class of density functionals are the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) methods,(11) which depend on both the electron density and its gradient. GGA’s are a significant improvement from LDA methods, since majority of molecular systems are spatially inhomogeneous and differ in comparison to a homogenous electron gas. Recently, new functionals that incorporate additional terms like higher density gradients or more specifically, the kinetic energy density, have been developed.(12,13) These methods are termed meta-GGA. Additionally, hybrid density functionals which combine the exchange-correlation of GGA’s with some level of Hartree–Fock exchange have also been developed.(14,15) Meta- versions of these hybrid GGA’s include a dependence on the kinetic energy density. All together, these functionals can be classified into rungs which Perdew and Schmidt(16) represent in a hierarchical form, commonly referred to as “Jacob’s ladder”. Moving up the rungs of Jacob’s ladder, there is a systematic improvement in the approximations of density functionals, such that each succeeding functional up the ladder possesses more accurate approximations than the one preceding it.

Jacob’s Ladder for 5 generations of DFT Functionals

There are a number of density functionals that exist and designing functionals that approximate the exchange–correlation energy term is an active area of research.(17) In chemistry, the Becke’s 3-parameter hybrid functional (B3LYP), which incorporates Becke’s exchange(18) combined with Lee, Yang, and Parr’s correlation functionals(19) is considered the go-to exchange-correlation functional for use in quantum chemistry calculations. It is among the most highly cited top-10 papers of all time(20) and is the most popular approximation in use in chemistry today — with a growing number of publications each year.(21) In 2007, an analysis of the percentage of occurrences of several functionals in journal titles and abstracts, from ISI Web of Science reported that B3LYP represented 81% of the total density functionals used in the literature.(22)

Here we have it folks, my brief blurb on DFT is complete! Thanks for reading!

References for Further Reading

- Young, D. Computational Chemistry: A Practical Guide for Applying Techniques to Real World Problems; John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Publication, 2001.

- Levine, I. N. Quantum Chemistry (5th Edition); Pearson, 1999.

- Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous Electron Gas. Phys. Rev. 1964, 136 (3B), B864–B871.

- Engel, T. Quantum Chemistry and Spectroscopy; Prentice Hall: New York, 2013.

- Kohn, W.; Sham, L. J. Self-Consistent Equations Including Exchange and Correlation Effects. Phys. Rev. 1965, 140 (4A), A1133–A1138.

- Jones, R. O.; Gunnarsson, O. The Density Functional Formalism, Its Applications and Prospects. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1989, 61 (3), 689–746.

- Kohn, W. Nobel Lecture: Electronic Structure of Matter—wave Functions and Density Functionals. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1999, 71 (5), 1253–1266.

- Van Houten, J. A Century of Chemical Dynamics Traced through the Nobel Prizes. 1998: Walter Kohn and John Pople. J. Chem. Educ. 2002, 79 (11), 1297.

- Pople, J. A. Quantum Chemical Models. Revs. Mod. Phys. 1998, pp 1267–1274.

- Frisch, M. J. et al., Gaussian 16, Revision A.03. Gaussian Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016.

- Perdew, J. P. Density-Functional Approximation for the Correlation Energy of the Inhomogeneous Electron Gas. Phys. Rev. B 1986, 33 (12), 8822–8824.

- Perdew, J. P.; Kurth, S.; Zupan, A.; Blaha, P. Accurate Density Functional with Correct Formal Properties: A Step Beyond the Generalized Gradient Approximation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82 (12), 2544–2547.

- Adamo, C.; Ernzerhof, M.; Scuseria, G. E. The Meta-GGA Functional: Thermochemistry with a Kinetic Energy Density Dependent Exchange-Correlation Functional. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112 (6), 2643–2649.

- Perdew, J. P.; Ernzerhof, M.; Burke, K. Rationale for Mixing Exact Exchange with Density Functional Approximations Rationale for Mixing Exact Exchange with Density Functional Approximations. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 105 (1996), 9982–9985.

- Ernzerhof, M.; Perdew, J. P.; Burke, K. Coupling-Constant Dependence of Atomization Energies. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1997, 64 (3), 285–295.

- Perdew, J. P. Jacob’s Ladder of Density Functional Approximations for the Exchange-Correlation Energy. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP, 2001; Vol. 577, pp 1–20.

- Burke, K. Perspective on Density Functional Theory. 2012, No. Xc, 1–10.

- Becke, A. D. Density-Functional Thermochemistry .3. the Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98 (7), 5648–5652.

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti Correlation-Energy Formula into a Functional of the Electron Density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37 (2), 785–789.

- Van Noorden, R.; Maher, B.; Nuzzo, R. The Top 100 Papers. Nature 2014, 514 (7524), 550–553.

- Fransson, T. X-Ray Spectroscopies through Damped Linear Response Theory, 2016.

- Sousa, S. F.; Fernandes, P. A.; Ramos, M. J. General Performance of Density Functionals 2007, 111 (August), 10439–10452.